Landscapes by Bargheer, Felixmüller, Heckel, Kirchner, Pechstein and Purrmann. Still lifes by Hofer, Kirchner, Nolde, Peiffer Watenphul, Purrmann and Schmidt-Rottluff. People by Eble, Hartung, Kirchner and Rohlfs.

Explanations of the individual works of art and artists in this exhibition:

In 1938, immediately before his involuntary emigration to Ischia, the Hamburg Secessionist Eduard Bargheer painted his grandiose North Sea mudflat landscape, drawing the flat horizon almost to the upper edge of the picture in an Expressionist manner and sketching a fierce landscape of mudflats at low tide, furrowed by tidal inlets in intense shades of blue and violet.

With a scholarship from the Basler Kunstverein, Theo Eble came to the Academy of Arts in Berlin in 1922 and was a master student of Karl Hofer there until 1925, in whose studio this scene of a standing and seated model was probably seen. Theo Eble does not paint them naked and in a pose, but in their normal clothes in a seemingly unobserved moment.

Conrad Felixmüller, a painter of the second generation of Expressionists who trained at the Dresden Art Academy, lived from 1918 to 1925 in nearby Klotzsche, practically a suburb, at Gartenstrasse 10. Here is probably a view from the window of this house, when ice and snow turned blue under an overcast sky and rising winter temperatures, and an evening sun from the right brought a few red spots under the clouds onto houses and paths.

In 1910, Erich Heckel and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner traveled to Hamburg and visited Gustav Schiefler, the spiritus rector of the early "Brücke" circle of collectors there, and in the following years often visited his country house in Mellingstedt, where Heckel depicted various Alster landscapes and the Mellingburger Schleuse in all techniques. As is so often the case in Erich Heckel's landscapes, the lower half of "Alsterlandschaft (Die Alster bei der Mellingburger Schleuse)" is taken up by a river, in this case the narrow Alster, which widens into a small pond. The opposite shoreline divides the composition horizontally in the middle. On the right, the Alster disappears a little higher under the trees that dominate the upper half of the picture, leaving only a little of the blue sky above free. Although the blue reflected on the surface of the water also dominates the lower half, the composition is overwhelmed by the green of the trees, a spring green. The park landscape becomes a picture of vegetation. The pure landscape was already of great importance in Erich Heckel's early work. It became dominant in the following decades until the 1950s. In it, he was able to develop his pure painting without being distracted by specific and defining objects or people. Here in the fiercely expressive brushstrokes of 1913.

The year 1914 was Janus-faced on both sides of July 28. Before that lay decades of great prosperity and immense technical, economic and cultural development in Central Europe, especially in Germany, whose capital Berlin became the driving force and world center of these events. Erich Heckel had also moved to this new center of European Expressionism in 1911. After this date in the summer of 1914, what was actually a local conflict in the Balkans suddenly grew into a world war: Austria-Hungary and Germany with minor allies against the rest of the world. Only a few (visual) artists immediately foresaw the hopelessness of the situation. Erich Heckel's biography states succinctly: "After the outbreak of war, Heckel volunteered to train as a nurse for the Red Cross in Berlin. However, he became friends with Franz Pfemfert, the publisher of 'Aktion'." A clear statement about Heckel's attitude: he would rather be a nurse than a common soldier. Considerations that Kirchner also made at the same time. His friendship with Franz Pfemfert meant that Heckel was an opponent of the war, as was Pfemfert himself, who always wrote against it in his magazine "Die Aktion" right up to the end of the war, bypassing the censors.

Did Erich Heckel create the painting "Park von Dilborn II" before or after July 28, 1914? The gray overcast sky, the predominance of restrained green tones, the dominant negative diagonal, the three pointed dark green accents in the upper right, probably poplars or narrow fir trees, but which appear here like the cypresses in Italian cemeteries, which Heckel knew very well from his intensively processed trip to Italy in 1909, all point to a later date. Heckel had, however, been with Heinrich Nauen in Dilborn in the spring of 1914. Of course, the painting may well have been created later in the Berlin studio. However, the luminosity of the colors of the Dresden years had already disappeared from his paintings since 1912/13, form and color often dissonant to the point of tearing, as if he too was formulating premonitions like Ludwig Meidner at the same time. In 1914, Heinrich Nauen painted a series of views of the park in Dilborn in a very similar color scheme but with more harmonious forms. Heckel also painted a series of six paintings of the park and the surrounding landscape of Dilborn. Heckel's exploration of form comes close to a breaking point in these paintings, if only because of their proximity to the works by Nauen, before July 28, after which he fell silent. The few paintings of the following years were characterized by the experience of war. In this painting from the first half of 1914, Heckel, like Meidner, who worked with him in Berlin, recognized the tense, overpowering forces of the time in a visionary way. Powerful wedges penetrate the composition from the right and left and shoot even more sharply upwards behind them. Only on the left does a protruding tree attempt harmony, but it is already too dishevelled: a grandiose landscape world in the peripeteia of time at a moment in which what follows was not yet recognizable.

In the spring of 1922, Erich Heckel stayed in the Salzkammergut and this painting "Mountain Landscape" shows the 2,713 m high Watzmann, the central mountain range of the Berchtesgaden Alps, in the background. After a brief resurgence of expressive form and color in Heckel's work after the end of the war, his form calmed down in the "Reisebilder" of the 1920s, following reality again, but only in its basic outlines. Generous, two-dimensional fields of color still stretch between them without any approach to New Objectivity precision. The color itself retains its expressive autonomy, in the landscapes often a strong green-blue sound, here with pink trees and also pink scree fields in the blue of the picture-dominating peak, which rises into the white clouds. Heckel is making his own personal contribution to post-Expressionist art. Despite its high degree of independence, this can certainly be apostrophized as Magical Realism, which is characterized by a high degree of sobriety and clarity and thus has nothing in common with the Romanticism repeatedly invoked in comparisons.

In the 1950s, Erich Heckel spent several summer months working in the Engadin. Often at high altitudes above the tree line and in all weathers. In these Engadine mountain landscapes, Heckel was not interested in heroic mountains and grandiose cliffs, but in the solitude and desolation, the great tranquillity and the reflections of the weather in the landscape, its play of colors on the rocks, slopes, Alps, waters and above all on ice and snow, which he knew how to create like no other with the post-expressive means of Modern art . On these mountain slopes, whose rocky peaks - here in "Berghänge (Berghänge bei Corviglia)" the "Trais Fluors", the Three Flowers near Celerina - grow out of wide slopes, an all-encompassing diffuse pink evening light plays on the bare stone and on the greenery, which becomes denser towards the bottom, even in the bright clouds above, perhaps intensified by reddish Scirrocco dust from the Sahara, which can be particularly noticeable at the heights of the Alpine ridges. A typical and exemplary painting from this Engadine group of works by Erich Heckel, which is dedicated to that zone of the earth in which man can usually only be a short-term guest.

The "Vegetable Still Life" from 1943 by the Berlin painter Karl Hofer is probably not one of Hofer's repetitions of destroyed paintings that began after the studio fire of 1943. Rather, it is probably an authentic work from this period. If Hofer did not lose sight of Cézanne in some of his other still lifes from this year, the old masters of the Netherlands seem to have been the inspiration here, naturally all in the brushstroke and the colorfulness of Hofer's late expressive new objectivity. Cauliflower, green and red kohlrabi, peppers: vegetables that could ripen in and around Berlin in the late summer/autumn of 1943. Except for the lemon, which probably came from the south, and a type of cucumber in a curved shape on the front right, or perhaps "Shotis Puri", a special Georgian bread.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner met the forest warden and dancer Hugo Biallowons (Sensburg 1879 - 1916 Verdun) in 1914 as a close friend and companion of the archaeologist and art historian Botho Graef (1857 Berlin - Königstein 1917). In the same year he painted "Portrait of Hugo" The early death of Hugo Biallowons at Verdun in 1916 was a great shock to Kirchner. His partner Prof. Botho Graef died of a broken heart a few months later. The loss of these two pillars shook his mental stability through the horrors of the First World War, ultimately leading to existential fear and Kirchner's breakdown, illness and long stays in sanatoriums. This makes his artistic production during this time all the more remarkable. His most important works were created during these difficult, fateful years.

Technically, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner's painting "Tall Pines in front of a Hilly Landscape" is unique because it is painted on wood. Kirchner practically always used canvas for oil painting, only in a few cases cardboard. It is not unique, but it is nevertheless special: It is painted on both sides, once in the early 1920s and the second time in the early 1930s. However, this second painting, "Standing nude in yellow and pink" 1930-1932, Gordon 720 v., is obviously unfinished in this case and the overpainting should therefore really be classified as a rejection. However, the composition is also special or unique. Art history has known spiral, tall, lanky trees at least since the famous "Avenue of Middelharnis" by Meindert Hobbema. There are also a number of such tall, spindly trees, either individually or in small groups, which only have a small crown at the very top, in the work of Ferdinand Hodler. In this case, because this composition really is a special case in Kirchner's landscape painting, we can assume that Kirchner had Hobbema and Hodler in mind when he observed this motif in the Davos landscape and captured it for himself. After all, following in the footsteps of Segantini, Giacometti and Hodler, he had become the fourth great painter of Alpine landscapes in the Modern art , which he was well aware of. For this reason, he also had to devote himself to this special theme of solitary trees on tall, slender trunks. A task that he accomplished brilliantly and entirely to his liking. The taller of his two heroes even pierces the upper edge of the picture, as is usually the case with Kirchner: Kirchner's Davos landscape pure, in violent forms of green and brown tones under an equally violent blue and white sky.

In Ernst Ludwig Kirchner' s painting "Farmer Pulling a Wheelbarrow" from 1925, a Davos mountain farmer pulls a wheelbarrow up a slope to the left. His leaning figure dominates the painting. The slope in the lower and left part is already green and covered in purple crocus, while the landscape and trees in the background are still covered in snow. The vigorous and powerful movement of the farmer with the wheelbarrow from the bottom right contrasts with the counter-movement of a horse behind him, which is almost prancing down a path between patches of snow from the top left to the bottom right at a careful pace.

In 1925/26, Kirchner painted the painting in the first forms of his emerging "New Style", in which uniform areas of color penetrate the differentiated areas of color. After 1930, he overlaid these areas of color with parallel hatching in line with his late art theory. These are mostly in the diagonal from bottom left to top right, thus counteracting and balancing the counter-diagonal that dominates the composition.

After his definitive move to Davos, Kirchner continued or expanded practically all of his previous pictorial themes, particularly his landscape painting depicting the Davos mountains. After Segantini, Hodler and Giovanni Giacometti, he became the fourth important Alpine painter of Modern art. What set him apart from these three, however, and became a unique selling point for Kirchner, was his preference for the life of the mountain farmers of Davos, which he observed and depicted very closely. He created an extensive painterly monument to them in his work, thereby making a very significant contribution to the working life of the Modern art between the wars. This painting is a central example of this group of Kirchner's works.

A scene bathed in the blue of an early morning in the mountains, still without sunlight. Blue and pastel green dominate the center against the bluish white of the snow in the upper half of the picture and the violet and green of the crocus and the meadow in the lower half. Violet also appears in the shadows of the face, the horse and behind the trees in the upper right as a color bracket of the composition. Only Kirchner can achieve such a color harmony.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner 's "Still Life with Jugs and Candle" was acquired by Roman Norbert Ketterer from the artist's estate after he took it over from Kirchner's heirs in 1954. In 1960, it was shown in the touring exhibition of his collection through museums in Germany and Switzerland, with a color plate at catalogue. From 1968 to 2006, the painting was in a collection in Cologne.

Three vessels of strong red, two jugs, one filled, and a bowl with some fruit, surround a blue candlestick with a white candle, on an ochre-colored tabletop in front of a similarly colored wood, perhaps already carved, and a wall corner in various dark shades of blue. The colors are often intermixed with white, including in the brush signature at the bottom left, which Kirchner made with the lighter blue with which he outlined the candlestick.

A programmatic work in which the volumes - because that is what the objects of a still life are primarily about - are projected onto the surface. The later "New Style" announces itself.

The sight of a horse and its rider falling must have made an enormous impression on Ernst Ludwig Kirchner , so that he nevertheless depicted the experience in the small painting "Rider with Fallen Horse" using the means of his "New Style", which were actually completely unsuitable for such an event. The convulsive forms of the horse and the fleeing rider, still tumbling in the air, interpenetrate to form an almost abstract composition of form and color of abstraction-création, which Kirchner approached in these years.

The "Singer at the Piano" from 1930 by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner sits in the center of the picture in front of the piano keyboard, which she plays while she sings, and is surrounded by listeners and sounds jumping up and piling up from the keyboard, similar to the sound columns of today's displays in recording studios. A central and paradigmatic work of Kirchner's "New Style" of these years, which is certainly based on a concrete visual experience, but which also exhibits all the characteristics of an abstract composition of the European abstraction-création of these years, if one disregards the object of representation.

The same proximity to the formal language of the pan-European abstraction-création of the early 1930s applies to Ernst Ludwig Kirchner 's "Nocturnal Fantasy Landscape in Green and Black". Black intertwined shadows in front of a dark green landscape under a narrow strip of dark green sky with moon and stars. One of Kirchner's many Davos moonlit nights, which he also mastered in his "New Style".

In "Vase with Flowers ", Emil Nolde 's second year of the war in 1915, a small bouquet of violet flowers in a shimmering blue drinking-cup-like vase against a dark blue background wall on a red tabletop that divides the small painting in half is enough for an expressive still life. The vase is slightly off-center to the left, the scene is lit from the left behind the viewer, so that shadows are cast on the table and wall to the rear right. As a pure "flower piece", this is rather the exception among Nolde's still lifes and therefore of great urgency.

Max Pechstein painted these "Walliser Hütten (bei Saas Almagell)" in 1923 in a mighty lower view over the entire height of the picture in front of equally mighty 4000-metre peaks in the background on one of his trips to Switzerland in the 1920s, when he visited his friend, patron and collector Dr. Walter Minnich in Montreux. These huts still stand in the same position in the mountain landscape today. A comparison of the photographs reveals the expressive implementation of form and color, the monumentalization of a small and actually insignificant piece of architecture in fiery evening light on the reddish-brown wooden beams under a sulphur-yellow, roiling sky.

It is true that the initially almost naive painting of Bauhaus student Max Peiffer Watenphul had already dissolved in a nuanced way by 1922. With his stay in Mexico in 1924-25, however, his painting suddenly erupted in a fiercely expressive blaze of color that only blazed for a few years. The two still lifes "Large Still Life with Field Flowers" and "Still Life with Flowers" from 1924 date from this creative period.

Hans Purrmann, a pupil of Henri Matisse and spiritus rector of his school in Paris, the so-called "Académie Matisse" in 1908, was repeatedly drawn to Paris, the south of France, Lake Constance, Italy and Rome, although Berlin became his organizational and economic focus. There is no mention of a trip to Rome in his vita for 1925, but there is one for the spring of 1926 - a small but insignificant uncertainty in the dating of "Atelierausblick auf den Monte Pincio". According to Göpel 1961, the studio was located in the English Academy in Rome, Via Margutta 53. Purrmann condensed the experiences of Cézanne, Matisse and Renoir in intense, expressive color to create a very personal style in a southern light.

In 1935, Hans Purrmann was surprisingly appointed director of the German Artists' Foundation Villa Romana in Florence. A stroke of luck for the "degenerate" artist and non-Nazi, because his escape to a freer country, in which Florence in particular offered significant if ambivalent freedoms. The "Fountain of the Villa Romana" in the park of the Künstlerhaus with its antique-like display wall captures a summer's day in the freedom and beauty of 1938.

In July 1943, the Allies landed in Sicily. At the end of August, practically at the same time as the occupation of Italy by German troops, Hans Purrmann managed to escape to Switzerland. Before doing so, he once again painted the "View of the Boboli Gardens" and Florence behind them from the south, from the Villa Romana. One of the many declarations of love to this city, which had protected him in life-threatening times and which he now had to leave. Lighter shades of green mark the foreground, darker shades with many cypresses mark the middle ground of the gardens, in the green a few red spots of the roofs of the houses, then lighter blue marks the background of the Apennine chain and the sky above. From here, the light, the hope, lay in the north.

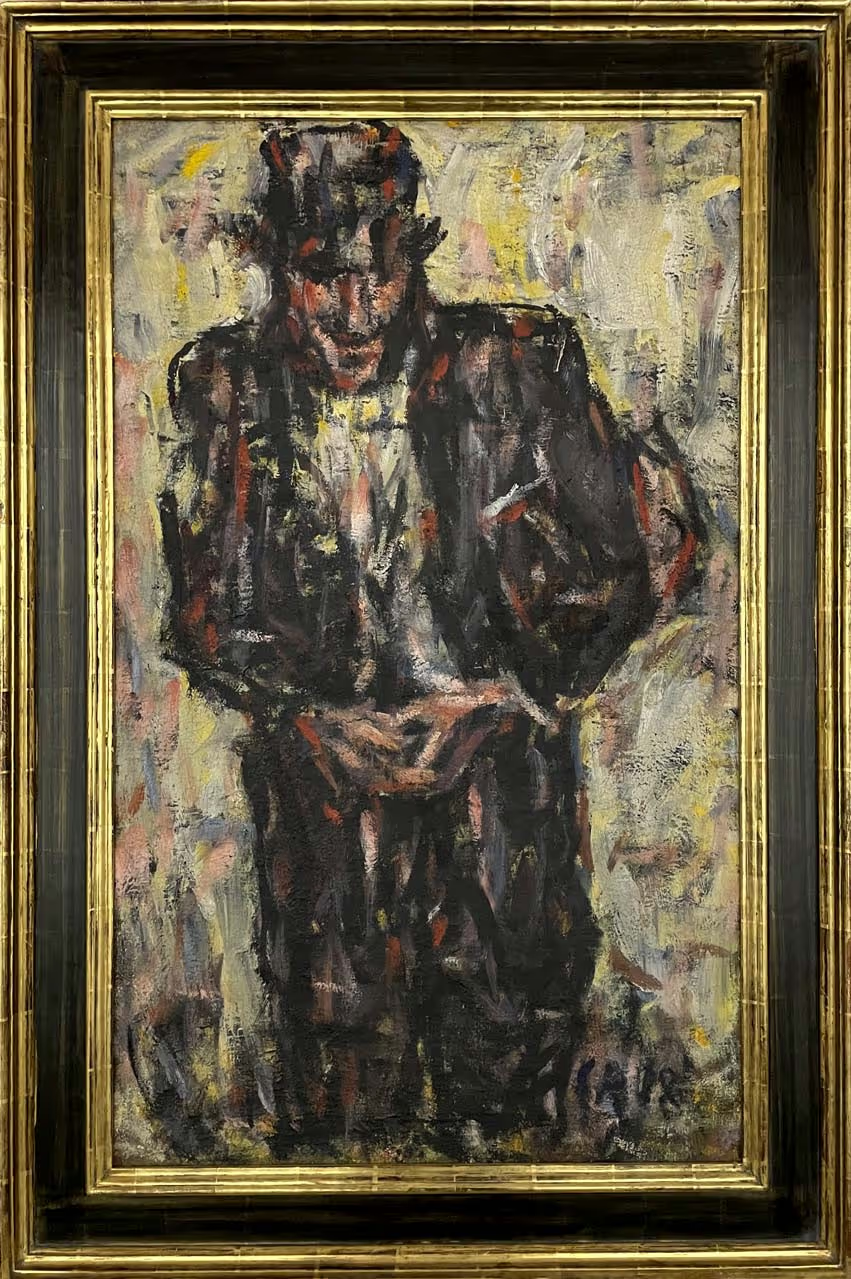

One of Christian Rohlfs ' "types" such as "Der Zecher", "Gehetzter" or "Spökenkieker", as they complement his scenes from the Bible and everyday life from 1915 onwards. (Otherwise, like most Expressionists, he was a magnificent painter of natural and urban landscapes). Rohlf's "types" were dubious but by no means exclusively negative, but also in the sympathetic realm of the all-too-human - just like his biblical and genre scenes.

This "crook", seen as a three-quarter figure, approaches the viewer with his head slightly lowered, submissive, looking at his hands in which he is turning something or perhaps counting money - so skillfully and quickly that one believes it is the correct remainder after payment, only to discover later that one has been cheated after all.

The figure in dark, mostly black, then red and blue, ochre for the incarnate, white for the shirt and the background in bright yellow and white strokes of color with a broad brush of the canvas. This impression is gained on closer inspection. Broad, straight brushstrokes, each up to ten centimetres long, are quickly placed next to and on top of each other, and when viewed from a greater distance, they no longer flow together in the eye to form a mixed color like the finer color dots of pointillism. On the contrary: although they do not become actual areas of color, they take on a life of their own, so that they can become devilish horns above the crook's forehead. Faun or Beelzebub, in any case a dazzling figure from colorful life.

The red of the blouse dominates the upper center of the picture. It is surrounded at the bottom right and left in the skirt and furniture, collar and hat by a lot of strong, dark brown contrasting blue, the wall in the background is turquoise. The girl's arms and face are also dark brown, surprisingly enough. In Christian Rohlfs ' work, expressive artistic realization and alienation were more a matter of color than form. The "girl in a red blouse" was hardly a dark-skinned girl; the place and the light where and in which Rohlfs saw the girl with a southern vest, perhaps on a rainy day, were dark.

Christian Rohlfs, born in 1848, was the oldest of the modern German artists of the first half of the 20th century. He lived two lives in succession, both personally and artistically. As a recognized painter and professor of German Impressionism, he saw a painting by van Gogh at Karl Ernst Osthaus in Hagen in 1902, which became a Saul-Paul experience for him. His personal expressionism was born, which he consistently realized until his death in 1938.

In addition to his natural and urban landscapes (Soest) and floral still lifes, he was interested in human existence in biblical scenes, in "types" such as "Crooks", "Spökenkieker", situations such as "Hounded Man", "The Terror" or professions such as "Violinist". These themes - including the biblical ones - were reduced to a moment, an existential one, as here in "Singer I". She stands on the left of the picture as a three-quarter figure in a dark red dress with a white collar or scarf, her hands outstretched in front of her body as if she were declaiming. She actually appears to be singing with her head turned slightly to the right. Three male figures, one on her left and two on her right, are listening to her, as is a woman leaning forward at the bottom right.

A moment of excitement: The dark red-blue sound with a slightly lighter dab of red in the hat of the listener on the right, the astonishing brown of the isocephalic row of heads above, these darks are countered by a screaming white in heavy brushstrokes around the heads, in the scarf and shirt of the person standing in the middle and the blouse of the bent listener on the right. Obviously, the highest notes and the highest excitement are being sung.

The themes of Christian Rohlfs ' depictions of people are almost inexhaustible and full of remote oddities, but here they are very simple and close in "Lord and Lady", or are they not? The woman stands in a simple red sack dress, the man in an equally red waistcoat with white trousers and a long white coat strides out in front of her and looks her in the face, converses with her, wearing a black top hat. He offers her his right arm. She hooks it. Some strange figures appear behind her on the left. Is that a child on her left? Behind the man on the right, an unclear background. The whole sheet is dominated by red watercolor, with brown tints on the left, a little blue in some places, the pen and ink creates the structure of this scene of a gentleman and a lady, the exact meaning of which is left to our imagination.

On medical advice, according to which he was recommended longer stays in the south, Christian Rohlfs discovered his "Giverny" in Ascona in 1927. He spent spring and summer in the "Casa Margot" there until his death. Just as Claude Monet's water lilies are at once dissolution and condensation as well as the autumnal, cheerful glow of a mature age, which can appear ever more fleeting, ever lighter without losing its effect, so too the landscapes of Lake Maggiore and Christian Rohlfs' southern flowers atomize into ultimate lightness. More and more color and form is taken away, any excess added is wiped or brushed away again. Calla - the beautiful one - in "Callas on a red background" still provided Christian Rohlfs with health and artistic consolation in 1936, even though the veils were becoming thicker and thicker.

Floral still lifes and individual blossoms of special flowers were Christian Rohlfs' great love. A special feature of his floral still lifes is that the vase and bouquet do not stand out completely from their surroundings and background, but rather communicate the colors and structures of the flowers to the entire surrounding space. The entire surface of the painting thus becomes a single frenzy of colors and shapes. This is also the case in "Iris in a Vase".

Karl Schmidt-Rottluff wrote to a friend after the end of the war in 1945: "All that remained was an unimaginable chaos that took the last of our strength to sort out. We were among the survivors, but not much else is left. The largest and best part of my pictures were lost in Silesia, so I feel like a legend myself." The sixty-year-old began again together with his wife Emy, strengthened by their common path since the "Brücke" in Dresden, and he tried something new again: in his art, he reacted to the changed world situation with a further stylistic stage in his work. In life, it was all about reconstruction, in which he and his wife were involved in a very special way with the founding and construction of the Brücke museum in Berlin in 1967. When he died in 1970, he had created an extensive late work which, without denying the expressionist background, responded to the demands of the present, as this still life, one of the strongest works of his late style, proves.

First of all, there is one of the few relics, "Blauroter Kopf (Panischer Schrecken", a sculpture carved in spruce wood by Schmidt-Rottluf from 1917 (Wietek 31, today "Brücke"-Museum Berlin). In the cellar of his studio house, this head, modeled on African models, survived the bombing and now stands on a small table in Schmidt-Rottluf's home next to a Dieffenbachia pot, an empty vase and other objects in front of painted canvases leaning against the wall. The objects are highly abstract and framed by contour lines, some of which take on a life of their own: This was also how the younger ones painted in 1949, if they had not already switched to complete abstraction by 1948 at the latest, like most of them. Only a few years later, this style was vulgarized for all purposes and was remembered less fondly by a generation as the so-called "kidney table style". Even good art can be misused. Here in this painting, however, Schmidt-Rottluff does more than just take up contemporary tendencies. At the same time, he remains completely true to himself. This is shown not only by the power of the forms, but above all by the tremendous power of the colors that have always characterized his work. Here he is able to enhance it once again. A grandiose still life.