According to Socrates, to be in dialogue means to create a common reality. One's own habits and those of others are examined and weighed in direct conversation with one another, and one's own knowledge and that of the other is brought to light. According to its Greek roots "diá" (through) and "légein" (to tell, to talk) the dialogue is understood as a "flow of words", translated from the Greek "diá-logos". However, the literal exchange that creates relationships with the other in its here and now can also be a figurative one: Where the spoken word reflects the attitude of its speaker, the work of art can visually express the inner frame of its creator. When two artists are brought into direct juxtaposition with each other, this can miraculously produce an exchange, a "conversation" between colors, techniques, and styles that may even be considered equal to the spoken word.

The exhibition "Ernst Ludwig Kirchner & Georg Baselitz in Dialog" explores precisely this fruitful moment, which can arise in the synopsis of two artists and which is inherent in a surprising number of new ways of viewing. Kirchner (1880-1938) and Baselitz (*1938) influenced and continue to influence entire generations of artists in their oeuvre, which was created separately from one another, and prepared the way for an art that was colorful, provocative, and consistently rebelled against the traditional and developed new modes of expression. The often different results of this creative work, to which both artists devoted their entire lives, will, however, in their dialogue with each other, also reveal one thing to the visitor: a common reality.

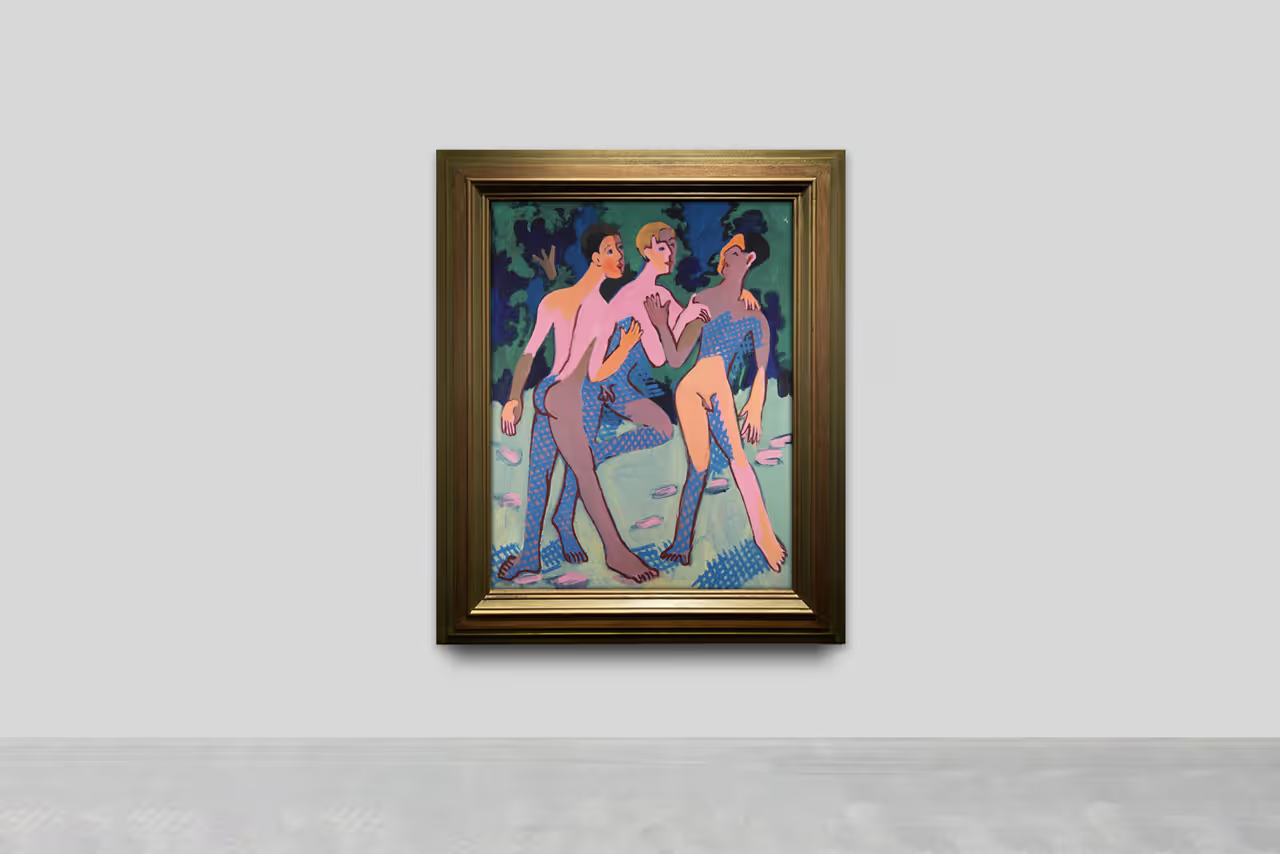

During the manifold experiences in and around the years of the First and Second World Wars, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner's work bore witness to the attitude towards life of an individual and the hope of an entire generation. Like no other, Kirchner captured the light-heartedness of his Dresden days and the briefly happy Berlin days in pulsating big-city scenes, in front of cheerful vaudeville backdrops, through people playing by the lake or moving freely in nature nude . With the same conciseness, however, he also sketched his own turmoil during the war of 1915 and its dramatic consequences in melancholy, dreary self-portraits. Kirchner finally found an inspiring new beginning in the seclusion of the Swiss mountains around Davos, which offered him a refuge until his death and inspired the development of his "New Style" in the 1920s.

What unites Kirchner's paintings, drawings, woodcuts and sculptures is a unique use of color, rather a "richness of color" that, contrary to naturalism, renders what is seen in expressive reds, blues and yellows, and later, often in shades of pink and brown, in a highly abstracted manner. Rough, woodcut-like forms, the dissolution of traditional perspective and emphasis on the fleetingness of the moment not only became Kirchner's stylistic hallmark, but also developed political potential at the time: "With the belief in development, in a new generation of creators, [...] we want to create freedom of arms and life for ourselves against the well-established, older forces."1] The birth of German Expressionism coincides with the artists' association founded by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and his friends Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff in 1905: "BRÜCKE". This association brought about a radical change in artistic production that broke with previously conventional modes of expression and placed the focus on the artist's own experience.

As a radical avant-gardist of a European Modern art , Kirchner laid down his rebellion against the establishment early on in the program of "BRÜCKE" and always remained true to it in his "aggressive deformations" of the given. What Kirchner showed for the spirit of the time in terms of unconventional design culminates definitively in Baselitz's "Kunstlosigkeit," the rebellion against "good taste" that expressive art continues to think.

Georg Baselitz is considered a polarizing artist who contributed to a radical upheaval in art history in the mid-20th century with his art form, offering a way out of contemporary abstract painting. Even the classification of his style was difficult, so one wavered between Surrealism and Expressionism, a little later his art was assigned to "Neo-Expressionism", although the term had a rather negative connotation. Thus, the artist always resisted being labeled a neo-expressionist, just as Kirchner refused to be called an expressionist.[1]

It is not only this rejection of "pigeonhole thinking" that unites the two artists, who are separated by half a century. Georg Baselitz, actually Georg Hans Kern, was born in Deutschbaselitz in Saxony in 1938, the same year Ernst Ludwig Kirchner died in Davos.

In fact, Georg Baselitz became acquainted with the works of Kirchner and the "BRÜCKE" artists only later, after his youth, because they were banned from all exhibition spaces because of the Bildersturm of the National Socialists. Only in 1983 direct references to the artist group "BRÜCKE" appear in the work of the master. But as Günther Gerken already formulated the question: "[...] should the Brücke-paintings be understood as an examination of the expressionist painting of the Brücke or only as a reminiscence of the artist group in the search for a model for a new expressive figure painting?"[2] Finally, it is not so much Kirchner's style that impresses Baselitz, but his attitude as an artist, as a human being, his outsiderness and not least his loneliness. With regard to Ernst Ludwig Kirchner's work, it is a matter of an affinity that can be traced in Baselitz's work over the years.

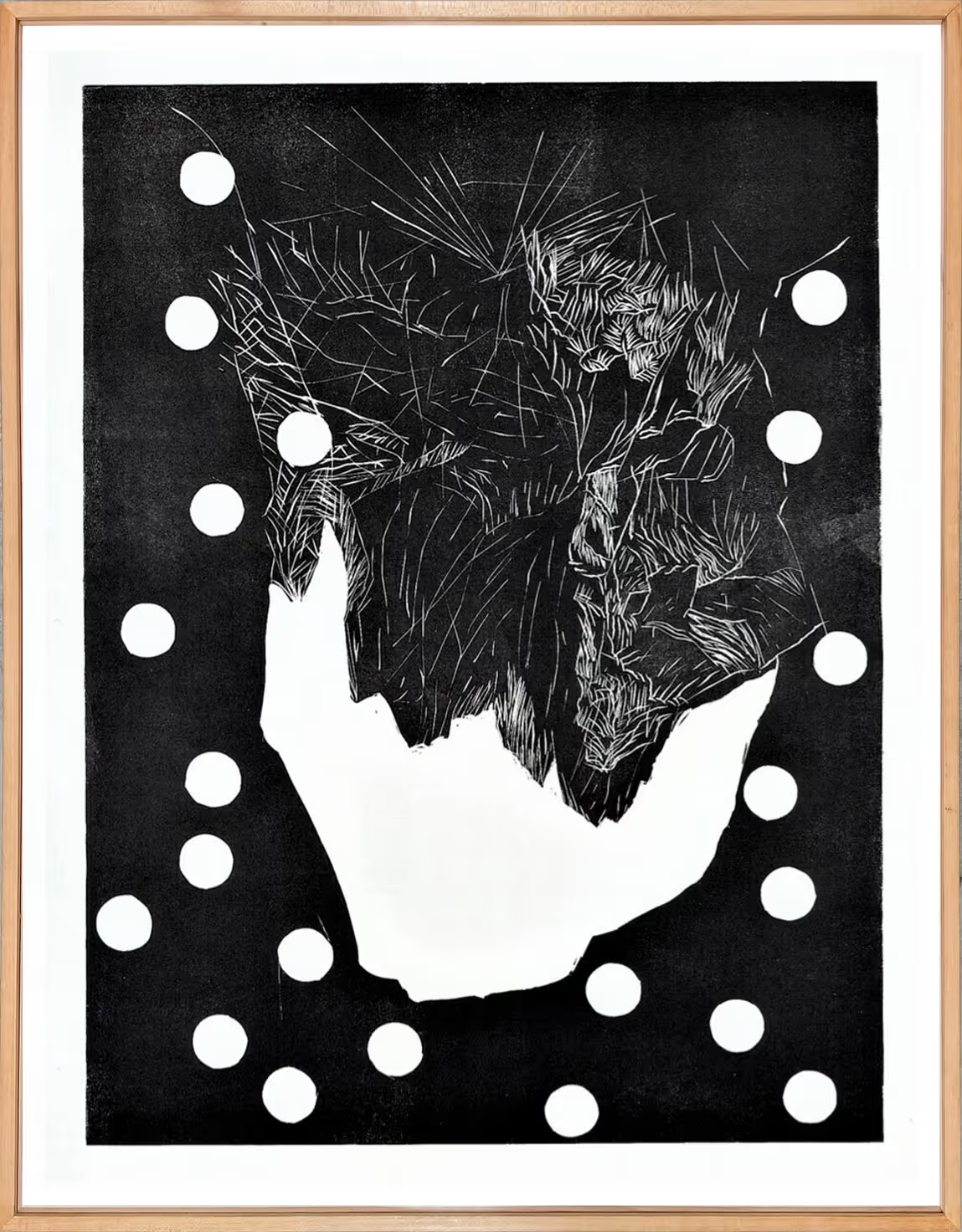

Thus, clear parallels can be seen in the graphic work of both artists, although, as Günther Gercken notes, their intentions are fundamentally different, because Baselitz's art, unlike Ernst Ludwig Kirchner's, is not a pictorial one, and he "develop[s] drawing as a structure that absorbs the motif, from itself. In doing so, the variation of form, unlike in the contracted pictorial language of the Expressionists, ranges from the utmost reduction of pictorial signs to mannerist squiggles and overload."[3]

The drawings of both artists are determined by the spontaneous grasp of sensory impressions, of what is observed and felt, and especially by the speed of the working process. This is equally evident in Baselitz's drawing "Bushes" from 1969-70 as in Kirchner's "People under Trees (Blühende Bäume)" from 1909.

A common technique of the two artists is found in the woodcut. While this was one of Kirchner's most important means of expression in graphic design, especially the "BRÜCKE" artists, Baselitz revived the 16th-century Clair-Obscur color woodcut, unusual for the time, in 1966.

Meanwhile, the motifs of the two also seem to overlap: man in the focus of creation. However, while nature occupies an almost equal position in Kirchner's work, Baselitz's motifs are mostly created by destroying existing images. The artist does not even stop at his own images, as the series "Remix" shows, in which he revisits past motifs from his œuvre and turns them into a kind of representation of an interaction with his own past.

Despite the many stylistic transformations to which Georg Baselitz's work has been subjected over the decades, a unified, unmistakable body of work has emerged that, with its individuality and uniqueness and, in particular, its innovation, is entirely in keeping with that of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner.

The dialogue between Georg Baselitz and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner is rounded off in the exhibition by sculptures by Daniel Spoerri (*1930). In turn, his heads and animal-like creations, created from assemblages, create a motivic link within the oeuvres of all three artists and at the same time enable a new view of the works of Georg Baselitz and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner.

Susanne Kirchner and Katharina Sagel